It is usually a good idea to stick to what you know. The values and norms we are socialised with provide support and orientation in our lives. But one trip to Japan is all it might take to turn your sense of values and norms on its head

When in Rome, do as the Romans do

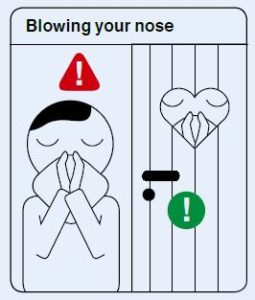

It is usually a good idea to stick to what you know. The values and norms we are socialised with providesupport and orientation in our lives. But one trip to Japan is all it might take to turn your sense of values and norms on its head … One of the sentences we hear all the time from our parents as we are growing up is: “Stop sniffing and blow your nose!” In Japan it is the other way around. Here they say: “Put away that handkerchief and sniffle like everyone else!” The Japanese think blowing your nose in public is inconsiderate – after all, that is how germs are spread. That is why it is important in Japan to excuse yourself in order to blow your nose where no one can see or hear you. You should not sneeze in Japan either, if you can help it. If you have a cold, you wear a face mask out of politeness and respect to make sure no one else catches your bug.

It is usually a good idea to stick to what you know. The values and norms we are socialised with providesupport and orientation in our lives. But one trip to Japan is all it might take to turn your sense of values and norms on its head … One of the sentences we hear all the time from our parents as we are growing up is: “Stop sniffing and blow your nose!” In Japan it is the other way around. Here they say: “Put away that handkerchief and sniffle like everyone else!” The Japanese think blowing your nose in public is inconsiderate – after all, that is how germs are spread. That is why it is important in Japan to excuse yourself in order to blow your nose where no one can see or hear you. You should not sneeze in Japan either, if you can help it. If you have a cold, you wear a face mask out of politeness and respect to make sure no one else catches your bug.

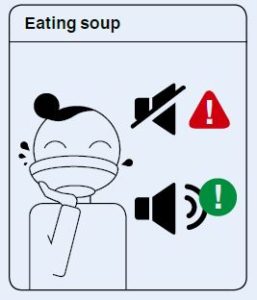

Another typical parental command at the dinner table is: “Stop slurping!” But if you do not slurp your soup in Japan, people are likely to think you do not think your soup is very tasty. Slurping is a welcome mealtime noise that sends your compliments to the

chef.

And should you rub your disposable wooden chopsticks together loudly and visibly before a meal to remove any splinters, you have just committed the next faux pas. You should only do that to draw attention to how cheap you think the chopsticks are. Burping is also looked down upon in Japan.

When you go to pay the bill at a restaurant, there is another important cultural difference to be aware of: if you have been given good service in Germany and fail to leave a tip, you will quickly be seen as a rude pennypincher. In the land of the rising sun, however, the mood will quickly darken if you tip your waiter as you would in Western Europe to thank them for a job well done. Tipping is seen as an insult in Japan and is totally unwelcome. In Japan, attentiveness, friendliness and good service are taken as read and require no further thanks. Waiters (and taxi drivers) are even said to have chase dpatrons down the street to return a tip. And speaking of taxis: though you are used to opening the door yourself when you take a taxi in Germany as most drivers would never dream of hopping out to hold the door open for you, do not try to open the door when you are in Tokyo. In Japan the doors open all by themselves. They are powered by electric motors.

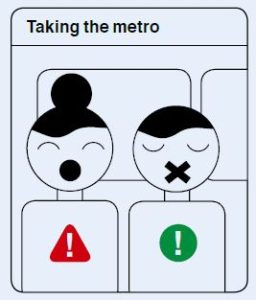

And if you decide to take the metro instead of a taxi back to your hotel after dinner, brace yourself for yet another cultural difference: you should never use your time on the train to make phone calls, which is often tolerated in Germany, and you should not speak loudly or about intimate subjects. On Japanese public transport, but also in public in Japan more generally, loud phone calls are frowned upon. What is more: believe it or not, the metro is a prime napping area! For the Japanese, it is completely normal to close their eyes and nod off on the train. Working people are on their feet early and work long hours. That is why signs on public transport ask the travelling public to put their mobiles on silent and refrain from phone calls on the go. The same goes for loud conversation and laughing.

If you are hungry or thirsty after a long trip, you will find plenty of snacks and beverages in Japan’s train stations. But remember two things: never count your change – you might as well just accuse the cashier of scamming you directly. And never eat or drink while walking. That is considered improper, as eating is highly important in Japanese culture.

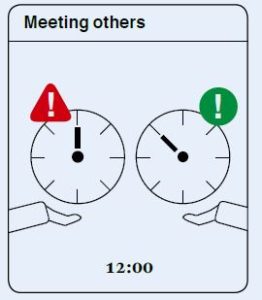

Recall the sentence “Be sure to be on time!” from your youth? You may have intuited by now that it works a bit differently in Japan. There is no such thing as the academic quarter (being 15 minutes late) in Japan. It is barely acceptable to show up on the dot at the arranged time. It is better to turn up five to ten minutes early, or better still half an hour.

Recall the sentence “Be sure to be on time!” from your youth? You may have intuited by now that it works a bit differently in Japan. There is no such thing as the academic quarter (being 15 minutes late) in Japan. It is barely acceptable to show up on the dot at the arranged time. It is better to turn up five to ten minutes early, or better still half an hour.

You should also strike the word “no” from your vocabulary during your stay. We have now arrived at the issue of direct communication, which we are used to in Germany, and the indirect communication of reading between the lines, which is preferred in Japan. But that is a long and very different story. Perhaps we

will get to it in the next issue..

Changes No. 7

Please click on the picture to open the Changes No. 7.

Download

Download the latest Changes as PDF.

Subscribe

Subscribe for the print edition of our customer magazine “Changes”.